The Wizard of Concrete Block

My fascination with concrete must have started in Rome in 1961 when I first visited the Pantheon and discovered that its phenomenal dome, completed in 128 CE, is made of brick and concrete.

The Pantheon, Rome, Italy

Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1908 Unity Temple constructed entirely of concrete in Oak Park, Illinois and deemed one of the most important buildings in the world[1] cemented my interest in this amazing building material. Like the Pantheon, Unity Temple’s concrete had to be mixed on site. In fact, the, “first load of ready mix was delivered in Baltimore, Maryland in 1913. The idea that concrete could be mixed at a central plant, then delivered by truck to the job site for placement, revolutionized the concrete industry.”[2]

My Queen Anne house dates from 1907 and while only the walkways, foundation and block wall at the sidewalk use concrete, it shares with the Pantheon and Unity Temple that the concrete had to be mixed on site. It is likely Seattle didn’t have ready mix until 1918.

Sear’s Wizard for making concrete blocks

The random pebbles and inconsistent look of the concrete walls of my foundation are proof of mixing on site, but it is the concrete block wall that has attracted my attention ever since we moved in thirty-seven years ago.

I first learned about these blocks in graduate school when studying the history of Sears Roebuck and Company’s Kit Homes and learned that the kit included The Wizard. That meant that even the average homeowner could produce perfect blocks for walls and foundations quickly and with almost no training. You just had to pack a bit of wet concrete into a mold, give it a squeeze in the Wizard, open the machine and put the concrete out to dry. If your machine had a bunch of bottoms, you could make your blocks in relatively short order. The Sears catalog had several different mold faces, so you weren’t obliged to use the same design as your neighbor.

The twin to my house is just up the block at 1512 First Ave. N. It was completed by Fred Nelson about six months after mine. The twin has a concrete block foundation. Over the summer of 1907, Nelson apparently decided that he preferred the look of concrete blocks to the solid walls of our foundation. It may also have been that Nelson built our house for a client while the later house he put up for himself and preferred the more decorative surface. Perhaps Nelson moved his Wizard or its equivalent from site to site, or maybe he just bought the concrete blocks from somebody in business.

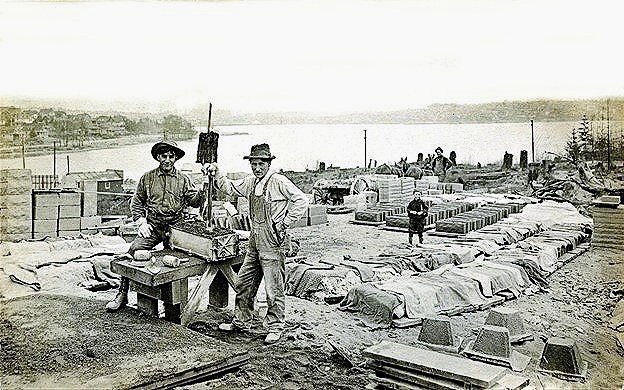

Concrete being forced into a form. This photo shows a yard where blocks may have been made for resale[3].

You can then imagine my delight when Clay Eals who partners with Jean Sherrard on Paul Dorpat’s Now and Then page in Pacific Magazine sent me this photograph that Theresa Anderson had discovered. There on the edge of a Seattle lake sat two men amidst a whole bunch of decorative concrete blocks, cheerfully displaying concrete in a mold. The little boy has a big smile too. Maybe the block in the mold was the final one for this site, or just maybe these fellows were making the blocks for resale.

1907 concrete block at my home

In all fairness, I should warn you that most of the decorative concrete blocks in front of our house are now covered with a thick veneer of English ivy. When we moved in, we decided that the decorative blocks were plain ugly. The ivy hides the blocks while we wait for the wall to collapse and to build a prettier one.

How we hid it

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akDqNgXqvKA

http://trowelcollector.blogspot.com/2016/06/concrete-block-molds.html

[2] History of Concrete - Concrete and Cement History Timeline - Concrete Network

[3] Thanks to Theresa Anderson for sharing this undated photo she found in a box hidden away in Alpine, Washington.