A Bloom with a View: The community gardens of Queen Anne

Photos by author unless otherwise noted.

Seattle is a haven for community gardens and gardeners. Well before the p-patch era, the city experimented with victory gardens, school gardens, and feeding programs for the poor. In difficult times, neighbors have banded together to find ways to help others. Much of the impetus for community gardening comes from what once was termed the “food dilemma” or what today is often referred to as food insecurity. In 1973, at the height of the “back to the earth” movement, the City of Seattle launched its P-Patch program. The P in P-Patch honors the Picardo Farm in the Wedgwood neighborhood which became the first p-patch. Seven more were created the following year, and today the program has grown to 91 gardens, as well as a couple of urban farms.

To win designation and support from the city, a p-patch must grow only organic produce, must be open to the public, and must operate with volunteer labor. Gardeners pay a nominal fee for the use of small plots of land on which they may grow vegetables, berries, herbs, and flowers. Gardens typically also offer beds farmed communally for the benefit of food banks. Some have demonstration beds, you-pick orchards, and public art. The program quickly became and remains a model for community gardening around the country and the world.

The Queen Anne neighborhood boasts three p-patch style gardens, and (at least) one guerrilla garden. Another large p-patch lives just across 15th Avenue N.W. in the Interbay neighborhood.

Queen Anne and Queen Pea

Rich Macdonald is a Queen Anne resident and the former manager of the city’s p-patch program. In 2022, he showed me around the Queen Anne P-Patch which he helped establish. It is tucked away, out of sight from surrounding streets, roughly below Lynn Street. and between 2nd and 3rd Avenues N. There are several food bank plots and a couple of communal herb plots, in addition to 73 individual gardens. A row of trillium blooms along the south fence, plants which Macdonald obtained from a retired gardener at the Picardo Farm and propagated here. There is also a small orchard of apple trees.

Trillium at Queen Anne P-Patch. Photo: 2022.

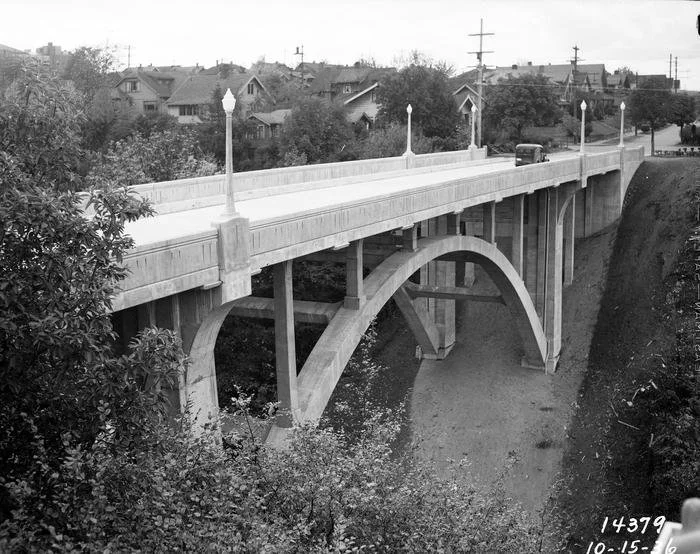

The Queen Anne P-Patch is situated on the southern tip of the Wolf Creek Natural Area, most of which is a steep ravine drained by Wolf Creek. In the years leading up to the 1962 World’s Fair, the southern portion of the ravine was used as a landfill for construction debris from the demolition of structures on the future Seattle Center grounds. Bits of rubble, including chunks of concrete, occasionally emerge from the filled and leveled ground. Anecdotal evidence of this history is corroborated by soil samples taken in the area and the dating of alder trees at the southern tip of the greenspace.[1]

The rebuilt McGraw Street Bridge above Wolf Creek Ravine. Photo: Seattle Municipal Archives, 1936.

Despite the unstable nature of the one-third acre, it became the object of desire for developers. Fortunately, neighbors advocated strongly for the site to remain open space, and, in the early 1990s, the city was able to purchase the land with bond funds and turn it into a community garden.

The view from Queen Anne P-Patch is of the peek-a-boo variety, a glimpse of Fremont to the north.

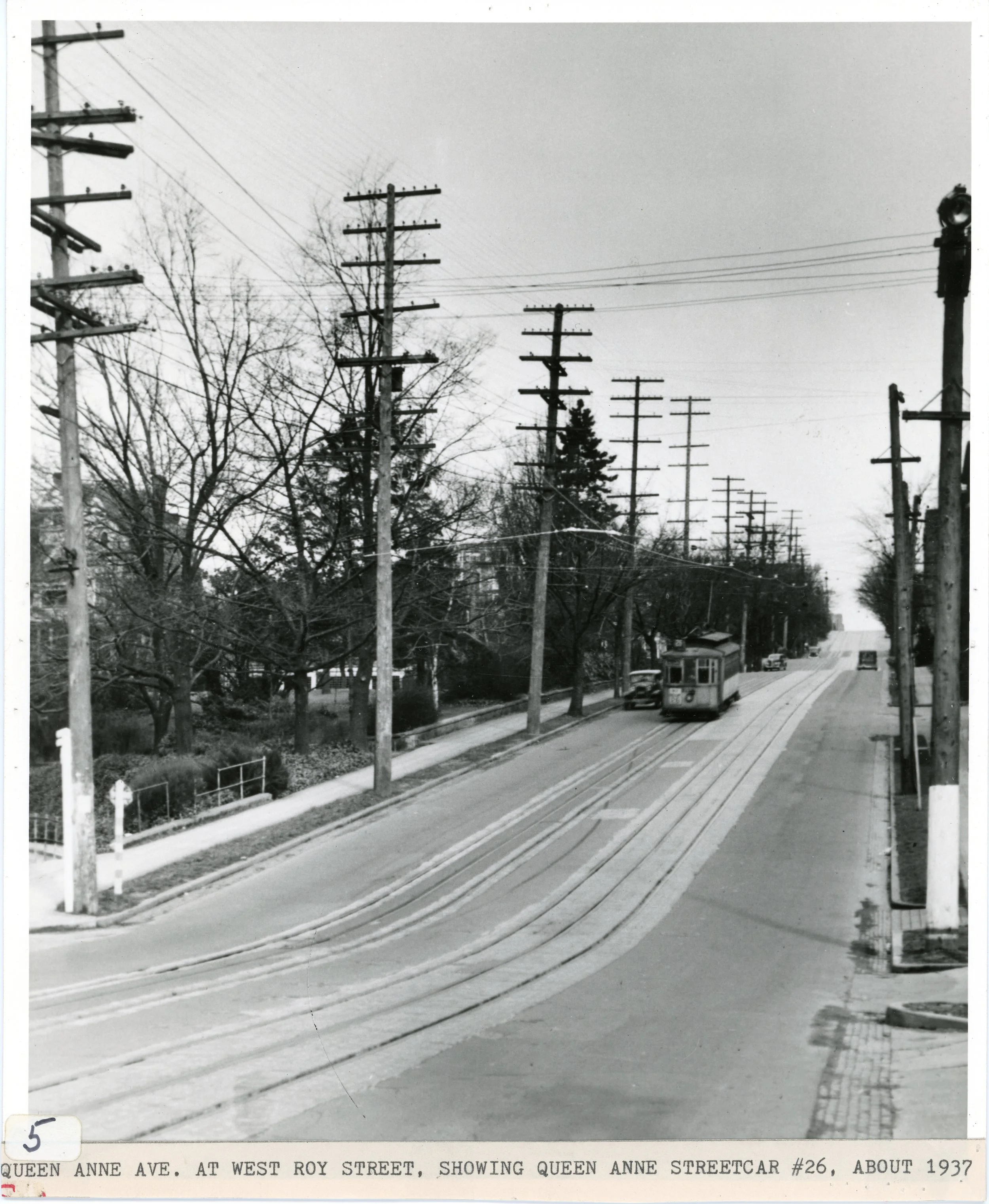

Queen Pea is a 34-plot garden on the eastern edge of the hill within Trolley Hill Park, both established in 2002. Trolley Hill honors Queen Anne’s half century of trolley service (1890-1940) and connects to the large Northeast Queen Anne Greenbelt. According to signage at the site, half the land for the little park was an abandoned City Light substation; the remainder was purchased with King County open space bond funds. On a clear day, one can see Mt. Rainier to the south from the garden; further vistas, of Lake Union and the Cascades, open up as one ventures into the greenbelt. The development of the green spaces here represents fulfillment of a suggestion made by the Olmsted Brothers a century earlier.

Queen Pea P-Patch in Trolley Hill Park. Photo: 2022.

Photo: Paul Dorpat Collection, 1937.

UpGarden: Higher Ground

Lower Queen Anne’s UpGarden also has a connection to the World’s Fair. This most unique of p-patches came into being in 2012, the 50th anniversary of the Century 21 Exposition. It is located on half of the top floor of the Mercer Street Garage, a structure built specifically for the fair and the new Seattle Center.

The UpGarden welcome arbor with nasturtium. Photo: 2022.

Gardeners, most of whom live within walking distance, have created 86 raised-bed patches. From their third-floor perch they can take in a 360-degree view of the Queen Anne neighborhood, including the Seattle Center and Space Needle.

View from the UpGarden. Photo: 2022.

Gardening on top of a parking structure comes with its own challenges. To begin with, all patches must be raised beds, since there is no subsoil. And the dirt that is poured into the beds must be lightweight: no clay or heavy compost. Water leakage into the parking tiers below has been an issue. Gardeners have made herculean efforts to re-configure their garden spaces and irrigation practices to mitigate leakage and allow access for garage maintenance.

The UpGarden office in a vintage Airstream trailer, part of the automotive theme of the garden. Photo: 2022.

Probably the greatest challenge, however, has been the temporary status of the garden, its fate wedded to a parking garage, and a relatively old one at that. Not only could the garden space be reclaimed for parking if the need arose, but the whole structure might be razed at some point in service to the Seattle Center Master Plan.

Fears for the future are well-grounded. In the fall of 2019, the tenants received notice to vacate. A professional hockey team, The Kraken, was coming to Seattle and scheduled to debut at KeyArena (now Climate Pledge Arena) in 2021. City planners felt the full top floor of the garage would be needed for parking. Moreover, the city would be rehabbing the somewhat decrepit nearly-60-year-old garage. A Seattle Center spokesperson was quoted in the paper as saying, "The decision has been made...we have to think about the primary purpose of the garage for all patrons of Seattle Center." [2] Long-time gardener Bob Grubbs summed up the feelings of the gardeners:

"For me, it's my backyard. You put down roots; you literally put down roots. And to do away with it was just a horrible idea! So, we decided not to go down without a fight and we started meeting and strategizing how to keep it." [3]

Unwilling to give up on their hard-worked plots, gardeners banded together and launched a "Save UpGarden" campaign. A petition was circulated, phone calls made. Lead gardener Barbara Oakrock invited incoming city council member Andrew Lewis to come to one of their meetings and hear about the garden. Lewis embraced the enthusiasm of the gardeners and went to bat with then-mayor Jenny Durkan to reverse the decision evicting the garden. On New Year's Eve, 2019, Lewis was sworn into office at the garden; he used the occasion to announce that the expulsion of the p-patch had been indefinitely postponed.

Building raised beds for the Upgarden, Eric Higbee and Nicole Kistler, working together as Kistler | Higbee Cahoot, designed the garden in collaboration with the gardening community. Photo: Eric Higbee, 2012.

While not currently threatened, the UpGarden's ultimate fate is tied to that of the structure upon which it rests. If and when plans to redevelop the area around the parking garage take shape, the UpGardeners may find themselves looking for a new home.

Interbay: Lower Ground

“You don’t just inherit dirt here, you inherit the past.” [4]

Yet another garden with a connection to the World’s Fair is the Interbay P-Patch, on the west side of 15th Avenue N.W., the dividing line between Queen Anne and Magnolia. This large area of low-lying swale, unsuitable for major construction, has seen many uses and attempted uses, from an Olmsted Brothers’ proposed athletic field for “the big boys and young men,” [5] to a planned but never built airfield, to today’s public golf course. At the time plans began for the World’s Fair, the site was a landfill. Fair organizers, panicking at the poor estimates of available parking for fairgoers, converted a large stretch of the fill into a parking lot by covering it with a heavy clay surface. Attendants were put in place. However, as the big day approached, local businesses around the fairgrounds opened up more parking, making the Interbay parking lot redundant.

The little-used Interbay World’s Fair Parking Lot. The site had been a landfill. Gilman Drive W. can be seen at right; Fishermen’s Terminal and the ship canal are at upper right. Photo: Seattle Municipal Archives, 1962.

Century 21 head honcho Joseph E. Gandy, in a post-fair interview, named the parking lot as one of his regrets: “At great expense, we created the now infamous Interbay Parking Area – which never had a car on it.” [6]

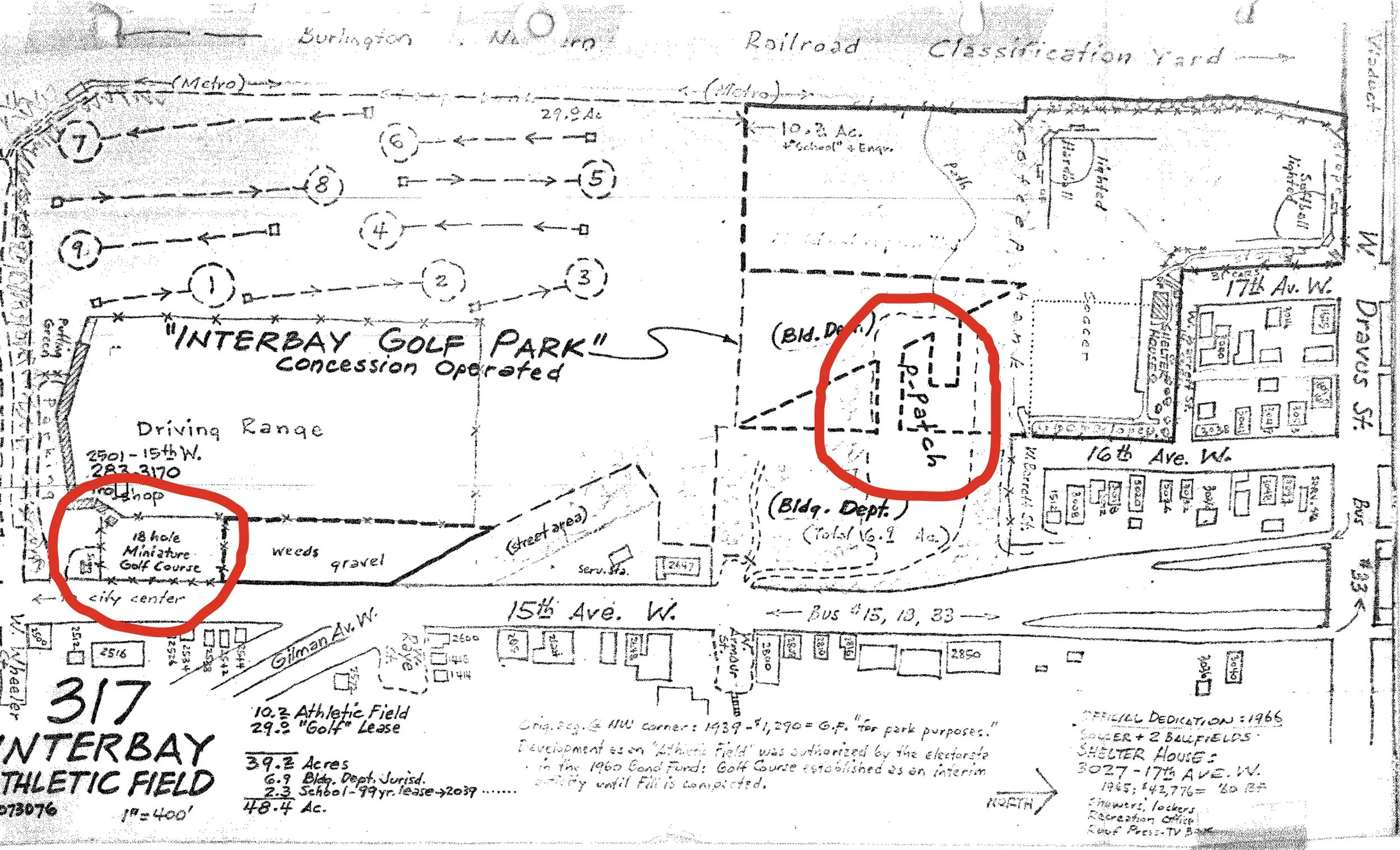

The leveled and covered landfill became the site of the Interbay Golf Park, according to one reporter, “almost without doubt the worst golf facility in the world." [7] A p-patch was established in the middle of the complex in 1974, just shortly after the city began the program. Rumor has it that some guerrilla gardening was occurring prior to that time on the site, along with phantom dumping.

Plan of the Interbay Golf Park, Don Sherwood Park History Sheets. The diagram shows the original location of the p-patch and the mini-golf course where the garden is currently located. Photo: Seattle Municipal Archives, approximately 1975.

The venerable Interbay P-Patch, now more than fifty years old, has had a storied and challenging history, being forced to relocate not once, but twice as plans for a renovated golf course took shape. Today it occupies the southeast corner of the city’s Interbay Golf Center, near the intersection of 15th N.W. and W. Wheeler Street, the former site of a mini-golf course. One of the larger of the city’s community gardens, Interbay contains 132 individual plots, as well as dedicated giving gardens, honeybees, and a large outdoor gathering space. Despite its location in a geological depression, there is a view to be had from the garden – of Smith Cove and cruise ships to the south.

Interbay P-Patch, view towards Smith Cove. The huge cruise ship appears much closer to the garden than it actually is. Photo: 2021.

Unsanctioned: Gilman Gardens

Gilman Gardens, an unofficial or “guerrilla” p-patch, occupies a strip of land in the median of Gilman Drive W., on the west slope of Queen Anne hill just two blocks from the Interbay P-Patch. The garden took root in 2013 when neighbors in the nearby condos and apartments decided to reclaim the land that had become a dumping site and an eyesore. Volunteers installed pathways and steps, rain barrels, and compost bins, and set up approximately 50 small plots. Although not recognized as an official p-patch, the garden has been the recipient of some small grants from the city for improvements, including the building of a tool shed. From the narrow garden one can obtain a nice view of Magnolia Hill.

Gilman Gardens, Sprite rain barrel. Photo: 2026.

Gilman Gardens, tool shed and rain barrels. Photo: 2026.

Although community gardens are almost universally seen as a blessing, they come with many challenges. Neighborhood groups have had to contend with the ordeals of finding a suitable site and maintaining it in the face of climate change, including droughts, vandalism, unexpected catastrophes such as the Covid pandemic, and, perhaps most importantly, competing uses. Three of the gardens mentioned here appear to be set for life, thanks to public ownership. However, the UpGarden and Gilman Gardens continue to occupy a grey area. The sunny side of the story is that community activism can go a long way toward creating and keeping these gardens blooming.

Sources

Much of the research for this essay draws from the Seattle Community Gardening History project, an oral history of the city’s public gardens I carried out in 2021-23. This effort included interviews with Bob Grubbs of the UpGarden, Rich Macdonald of the Queen Anne P-Patch, and Donna Kalka and Ray Schutte of the Interbay P-Patch. Additional information came from newspaper research, Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods, and HistoryLink.org.

For further information about community gardening in Seattle and the history of the p-patches, see Rita Cipalla’s essay on HistoryLink.org: https://www.historylink.org/File/20662 or Eleanor Boba’s community gardening history blog: https://seattlecommunitygardening.blogspot.com/.

Footnotes:

[1] King Conservation District, Wolf Creek Ravine Forest Stewardship Plan, 2025 https://kingcd.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/WCR_Forest_Stewardship_Plan_FINAL_2025-03-24-1.pdf

[2] Nicole Brodeur, “P-Patch atop Mercer Street Garage evicted to make way for hockey fans,” The Seattle Times, November 5, 2019.

[3] Bob Grubbs, Interview with Eleanor Boba, October 9, 2023.

[4] Donna Kalka, Interview with Eleanor Boba, September 25, 2021.

[5] Don Sherwood Park Histories, Interbay Athletic Field/Golf Course.

[6] Charles Dunsire, “Fair President Gandy ‘Tired To The Bone,’” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 22, 1962.

[7] Terry McDermott, “Interbay course needs rescue from rough,” The Seattle Times, April 16, 1996.