McAdoo’s Pool: A Legacy for the People

In a charming, family-friendly neighborhood lies an unassuming brown-brick Pacific Northwest Modernist building with appropriate signage which displays “Queen Anne Aquatic Center.” The Aquatic Center resides on 1st Ave W., and is perfectly complimentary to the Community Center, and McClure Middle School across the street, which displays many children’s art in the windows. This is an avenue and area that is important to so many people of all ages. Many families bring their children to this public space, housed in a subtly beautiful structure designed with intention for many people, in accessible, natural materials that merges the lumber and landscape of hilly Queen Anne, into the landscape of the West Queen Anne Playfield, the school, and sharply juxtaposed to the stately and charming Craftsman, Queen Anne, and Victorian single-family homes that envelope the pool.

The interior of the pool, with its paneling, might invoke the midcentury modern architectural designs that wove the natural aesthetics and materials that shaped Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Caribbean traditional architecture.

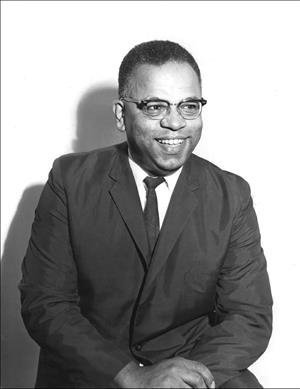

The Queen Anne pool was designed by famed Black architect Benjamin McAdoo, who was born in Pasadena, California in 1920, transferred from the University of Southern California to the University of Washington, and began his career as the first Black registered and practicing architect in Washington state after graduating from the architecture program in 1946.[1] McAdoo was a social, racial, and environmental advocate whose focus evolved from private homes into more accessible mixed-use residential buildings and public spaces after designing low-cost public housing in Jamaica on behalf of USAID.[2] The very existence and design of this pool in Queen Anne Aquatic Center is monumental and poetically beautiful, when the life history of Benjamin McAdoo, and the human history of Queen Anne, and Seattle are taken into consideration, which includes the power dynamics of pools and racially restrictive covenants.

Benjamin McAdoo’s family settled in Pasadena, California, in 1899, and ran numerous businesses, and were a well-respected family whose home was filled with intercultural furnishings, textiles, and artworks made by Japanese and Chinese craftsman [1] that may have influenced his style and aesthetics. Black, Asian, Latine, and Indigenous Pasadena residents all felt the sharp sting of segregation and limitations of wealthy Pasadena, and often shared commercial enterprises together. In Lynn Hudson’s book, West of Jim Crow, the Fight Against Californians Color Line, California had the most pools in the entire Unites States, and Pasadena pioneered Jim Crow laws limiting access to them.[2] In 1914, Pasadena opened its municipal pool, Brookside Pool to the “public,” for Whites only. Two sporting legends, Korean American Olympian Sammy Lee, and Jackie Robinson recalled restricted access and were only allowed to use the pool on one day a week, on Tuesday afternoons between 2 pm and 5 pm.[3] Young Benjamin McAdoo would have faced these same limitations growing up, swimming only in Pasadena on “International Day,” the singular day for all nonwhites in Pasadena.

Brookside Plunge on International Day, circa 1928. (Courtesy of the Archives at Pasadena Museum of History; Photo Albums Collection, Volume 59

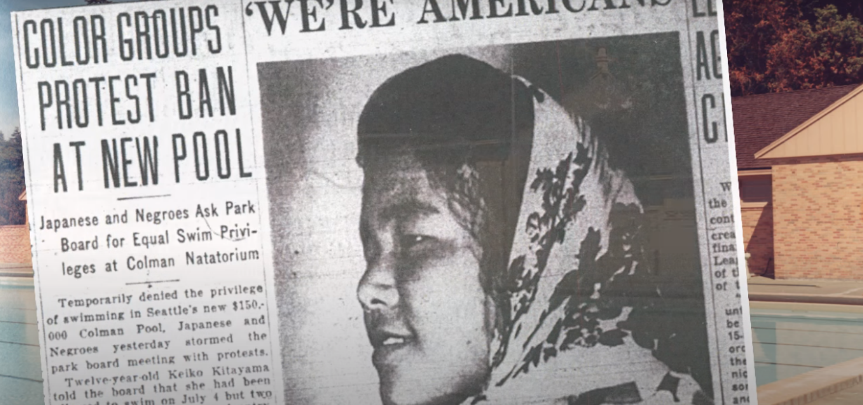

Seattle had its own Jim Crow laws limiting Black, Asian, Indigenous, and Latine access to swimming pools. Colman Pool in Lincoln Park and Moore Pool in the Moore Hotel had explicit signs that stated, “No Japs Allowed.” [1] These signs were implicitly stating that all swimmers of color were not allowed to swim in the public pools available to safely learn how to in controlled environments and were limited to learning how to swim in mud pools, and Lake Washington at Sandpoint,[2] Paula Block wrote in “The Power of the Pool…: that segregated swimming didn’t stop at municipal pools, but also local beaches.[3] Black and Asian children did not swim at the beach at Madrona Beach, Madison Park Beach, or Van Asselt Beach, which resides in the historically racially redlined and Black Central District.[4]

Screenshot from documentary film “Colman Pool: From Segregation to Immigration 1914-1944,” by Lee O’Conner.(Courtesy of Lee O’Conner, https://www.youtube.com/@leeoconnor5142 and Seattle Parks and Recreation)

Historically, Black and Brown youths have had less access to safe swimming waters and are part of a tragic disproportionate number of drowning deaths. These mortality rates remain disparate. In 2023, 12 people drowned in King County, and Black residents and nonwhite immigrants are 2 ½ times more likely to drown than white residents due to cultural barriers.[1] More often than not, many of the drowning deaths of the past were due to unsafe water currents at less regulated beaches in Sandpoint, in the Duwamish River, and in Rainier Beach. When Benjamin McAdoo moved to Seattle to study in 1944, Colman Pool was still segregated, but would soon lift its ban. This still did not mean that nonwhites had easier access to pools, nor did they feel welcomed or safe.

Kids in a Wading Pool at Collins Playfield circa 1940s (Courtesy of Ben Evans Recreation Program Collection [Record Series 5801-02], Seattle Municipal Archives.)

Dr. Quintard Taylor discussed how Christian Friends for Racial Equality, created by Black and white clubwomen, the NAACP, and the University of Washington’s black students’ direct demonstrations forced the city of Seattle to open its pools to nonwhite children on the eve of 1944.[1] Perhaps young McAdoo was one of those student activists, perhaps he was too busy working nights full-time, while studying. When McAdoo graduated in 1946, his office and built his business working in 1947 in his small kitchen in Seattle.[2] Seattle was still a very hostile place for Blacks to reside and freely enterprise in. Tom Fucoloro highlighted in the book Biking Uphill in the Rain, the Story of Seattle From Behind the Sandlebars the infamous “security map” created in 1936 by the Homeowners’ Loan Incorporation that color-coded the safety of neighborhoods as desirable, and placed Beacon Hill in the “red zone” as “hazardous.”[3] By 1945, over 10,000 Blacks occupied a region from Duwamish Bend to Yesler Terrace.[4] The first racially restrictive covenant in Seattle comes from the Windermere Neighborhood (April 1, 1929).[5] Queen Anne, was itself a “sundown” neighborhood in Seattle.[6] Sundown neighborhoods had to be free of Blacks after work ended, and there were many neighborhoods in Seattle that excluded Black leisure and life: Queen Anne, Magnolia, West Seattle, and the suburbs were off limits to Blacks after dark.[7] After 4 pm, while Benjamin McAdoo was designing stately mid-century modernist private homes for white Seattleites, he would not have been able to grab a bite to eat, nor drink, nor listen to music, let alone swim. Swedish Hospital, and Virgina Mason refused to let Blacks, Japanese, and other nonwhites into their hospitals[8] when McAdoo graduated from college. As late as 1968, Mr. McAdoo would have likely been escorted by the police out of Queen Anne and safely into his home in Bothell.

Photograph of the cover of the book The Negro Motorist Green-Book by JalexArtis. This guidebook appeared yearly between 1936 and 1966. It helped black travelers navigate "sundown towns" which black people had to leave by sunset. (Courtesy of Jalexartis, licensed under CC 2.0 Legal Code.)

On April 19, 1968, three weeks after the assassination of MLK, Jr, the City of Seattle unanimously passed Ordinance 96619 to end racially restrictive covenants and sundown zones.[9] In 1969, to provide equitable athletics and recreation to the city, the Model Cities Program was established. In 1970, the Medgar Evers Pool, named after the assassinated Black civil rights leader Medgar Evers, opened in the Central District.[10] The Medgar Evers Pool, built for Blacks in a historically Black neighborhood, was designed by a historically affluent white architect named John. M. Morse. Racist policies were still in play, despite the well-intentioned Model Cities Program. Admission fees continued to limit access to nonwhite families. Historically and currently, over 60 percent of Black children between the ages of 6 and 16 haven’t been able to acquire swimming skills.

Medgar Evers Pool 5,nd. (Courtesy of Seattle Parks and Recreation, https://www.seattle.gov/parks/pools/medgar-evers-pool.)

Despite the opening of the Medgar Evers Pool in 1970, many urban cities saw revisions of rules that still limited pools and parks to the nonwhite public. Many public pools created membership fees for unrestricted access, and many pools were filled in like the Moore Pool in Seattle. Other pools were made private “club pools” that hindered equitable access in the 1970’s.[1] The pool “privatopia” did not include Queen Anne in the 1970’s. Queen Anne, like the times, were changing and adapting. Michael Herschensohn wrote that the McAdoo Pool, located on First Ave, was initially controversial because it uprooted ten homes, and was the most expensive Seattle Parks pool built at that time.[2] Herschensohn’s expertise on landmarks notes the technological innovational design of McAdoo’s Pool. It was a historical break with Queen Anne’s traditional architectural styles at that time, which were predominately Queen Anne, Victorian, Dutch Colonial, and Craftsman. The pool is not as charming as a white-picket fence Victorian cottage, and that was intentional. McAdoo was modern, he wanted to uproot and break with the cozy traditions that did not make McAdoo, nor his fellow Black Americans feel safe. He wanted a structure that was influenced by the regional Pacific Northwest Modernist traditions, which blended the cultural architectural traditions of Africa, Asia, and Jamaica, that looks significantly different than the pool designed by white Morse for Seattle’s Black Community. McAdoo’s pool invokes warm, earthy, and earthly swimming within the inviting wooden interiors, that weaves the outside inside a climate-controlled space. McAdoo’s pool appeals to modern, practical, pragmatic generations.

Queen Anne Pool, August 21, 2015. (Courtesy of Seattle Parks and Recreation, https://www.seattle.gov/parks/pools/queen-anne-pool.)

Mr. Benjamin McAdoo built a pool in a neighborhood he would not have been able to swim in, or sleep in as a child, or as a young University of Washington student. Young Benjamin was only allowed to swim in his own Brookside Pool in Pasadena for 3 hours on only one day of the week. He built an innovative pool that broke from traditional architecture and traditions so that everyone could feel welcome to swim, swirl, and learn life-saving athletic skills. McAdoo’s pool is innovative, but the human history and intention behind that pool makes it historically significant. We should not forget the life history of the architect, of Queen Anne, and of human inequity. This is his legacy – a symbol of barriers broken, a pool for the people.

After returning to Seattle from work as the chief housing adviser for the U.S. Agency for International Development, Benjamin F. McAdoo Jr. told The Seattle Times in 1964, “Housing is the primary need of all the undeveloped... (The Seattle Times archives)

References:

1. Seattle Parks and Recreation. Pools-Parks. https://www.seattle.gov/parks/pools

2. Bothell, city of. 2023. “Black History Month, the Life of Benjamin McAdoo. City of Bothell News. February 3, 2023. https://www.bothellwa.gov/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=410

3. Deneau Denham, Sandy. 2023. “Benjamin McAdoo’s Lasting Legacy as an architect and an activist,” PNW Magazine, September 9, 2022, Seattle Times.

4. Pacific Coast Architecture Database. “Benjamin Franklin McAdoo, Jr. (Architect). https://pcad.lib.washington.edu/person/2167/

5. Pasadena Museum of History. 1984. “Interview with Benjamin McAdoo (August 24th, 1984, African Americans-California, Los Angeles, Pasadena Museum of History.

6. Hudson, Lynn. 2020. “The Only Difference between Pasadena and Mississippi is the way they are spelled,” pages 208-242, West of Jim Crow; the Fight Against California’s Color Line, University of Illinois Press, September 2020.

7. Thomas, Rick. 2018. “Throwback Thursday, Revisiting Our Racist Past,” South Pasadena News, June 14, 2018.

8, 9. DENSHO. 2015. “Segregated Swimming: Oral Histories of Japanese Americans and Public Pools,” August 2015.

10, 11. Block, Paula. 2008. “The Power of the Pool, issues of class, culture, and political priorities swirl,” Seattle Times, June 15, 2008.

12. King County Government. 2023. “Open Water Safety,” News Release, July 2023.

13. Taylor, Quintard, Dr. 2022. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era, University of Washington Press, 2022, pp 194-195.

14. Bothell, city of. 2023. “Black History Month, the Life of Benjamin McAdoo. City of Bothell News. February 3, 2023. https://www.bothellwa.gov/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=410

15. Fucoloro, Tom. Biking Uphill in the Rain, the Story of , the Story of Seattle From Behind the Handlebars, 2023, University of Washington Press, p 57.

16. Taylor, Quintard, Dr. 2022. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era, University of Washington Press, 2022, pp 194-195.

17. Seattle Municipal Archives. Restrictive Covenant from Windermere Neighborhood, April 1, 1929. https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/CityArchive/DDL/OpenHousing/covenant.pdf

18, 19, 20. Gregory, James. 2006. “Remember Seattle’s segregated history,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, Dec 11, 2006.

21. Seattle Municipal Archives. Open Housing, 1968. https://www.seattle.gov/cityarchives/exhibits-and-education/online-exhibits/seattle-open-housing-campaign

22. Historylink.org. N.D. Medger Evers Pool. https://historylink.tours/stop/medgar-evers-pool/

23. Wolcott, Victoria, W. 2019. “The forgotten history of segregated swimming pools and amusement parks, The Conversation, The University of Buffalo, July 11, 2019.

24. Herschensohn, Michael. 2014. Queen Anne Historical Society, “A Learning Moment: The Landmark Nomination of Benjamin McAdoo’s Queen Anne Pool,” January 2, 2024.

Jalexartis, N.D. Photograph of the cover of the book The Negro Motorist Green-Book by JalexArtis. licensed under CC 2.0 Legal Code

O’Conner, Lee. 2016. Screenshot from the film “Colman Pool: From Segregation to Immigration 1914-1944,” by Lee O’Conner. July 9, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/@leeoconnor5142 and Seattle Parks and Recreation

Seattle Municipal Archives. Kids Wading in a Pool at Collins Playfield in the 1940s. Ben Evans Recreation Program Collection Record Series 5801-02.