This Week in Queen Anne History

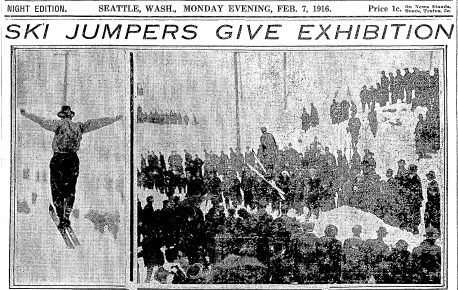

The February 6, 1916, Seattle Sunday Times announced that ski jumping and speed skiing today will be introduced to the Seattle public. The headline read: Men From North Jump With Skiis: Norwegian Residents of Seattle to Take Part in Winter Sport on Slide Down Queen Anne Hill [1]

The city had been digging out from under several feet of snow that began falling heavily on January 31st and continued for 48 hours, dropping 38 inches of on top of the two feet that had accumulated over an unusually cold January.

While the city dealt with the many setbacks imposed by the storm, a group of Norwegian-born Seattle businessmen saw opportunity in the piles of white to promote their beloved sport of ski jumping. Ski experts L. Orvald, John Olsen and John Sagdahl organized the event and chose Queen Anne’s steepest street, Fourth Avenue North between Halladay and Nickerson streets, to build the jumping venue. The men worked late into the night before the exhibition preparing the jump and landing slope.

Sagdahl explained to the Times, “The contest Sunday is in the nature of an experiment. For many years a number of ski jumpers from Norway who are now businessmen here have been attempting to create interest in the sport without success. We believe that skiing is one of the most thrilling sports in existence, both from the skier’s and spectator’s viewpoint.”

The timing of the experiment was just right to capture the public’s attention. After days of being snowbound, streetcar service had been restored and Seattleites were eager for some entertainment. The announcement in the Times promised excitement the likes of which most readers had never seen: The ski jumpers will travel for nearly three blocks on an incline of greater than 45 degrees in attaining speed for the leap. Reaching the bottom of the slope the jumpers will hurl themselves in the air, landing many feet beyond. More than a dozen experts have been entered into the event, many of whom hold records of various kinds for former jumps.

Event organizer John Olsen, who held a record jump of 110 feet, cautioned that he did not expect to jump more than half that distance because temperatures warming into the high 30s would make the snow adhesive and prevent the skis from attaining full speed. He predicted that the best jump of the day would be between 50 and 75 feet.

The announcement advised that the scene of the exhibition could be reached by any Westlake Avenue car running to the Stone Avenue Bridge.[2] From the stop at the south end of the bridge, spectators walked three blocks west along Westlake Avenue, passing the Fremont Bridge construction site, to arrive at the foot of Fourth Avenue North.

Despite the rising temperatures and lowered performance expectations of the ski jumpers, a large crowd of curious Seattleites gathered under a light drizzle of rain to take in the daring display. Olsen’s prediction proved slightly ambitious, with no jumpers reaching 50 feet. First place went to R. Gjolme, whose longest jump of the day was 43 feet. Second place went to event organizer, L. Orvald with a jump of 38 feet. Three jumpers tied for third place, J. Sather, O. Peterson and A. Falkstad each jumped 34 feet.

The success of the event was reflected in a steady increase of interest in skiing and ski jumping throughout the region. Between 1917 and 1924, Norwegian ski jumping tournaments were held over the 4th of July holiday at Mount Rainier’s Paradise Valley. From 1924 to 1933, the Cle Elum Ski Club held ski jumping tournaments that drew crowds of 3,000 to 5,000 spectators. A circuit of competitions thrived in the Pacific Northwest, including National Championships in Leavenworth, until the sport began to decline in the 1960s. The last Leavenworth tournament, a National Championship, took place in 1978. [3]

According to author and ski historian John Lundin, ski jumping was the most popular winter sport in the Pacific Northwest from the teens to the 1940’s, thanks to the region’s large population of Nordic immigrants. And Washington’s first jumping event was the one staged right here on Queen Anne Hill on February 6th, 1916.[4]

[1] “Men from North Jump with Skiis [sic],” The Seattle Sunday Times, 6 February, 1916, p 21.

[2] The Stone Avenue Bridge was a temporary trestle bridge with a center opening for watercraft that carried vehicular, pedestrian and streetcar traffic across Lake Union. The bridge, which stood from 1911-1917, was built to serve communities north of Seattle during construction of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and Fremont Bridge.

[3] John Lundin, “When the Northwest Was a Center of Ski Jumping in the US.” Nordic Kultur (2020) p 26.[4] Ibid, p 26.