Seattle's Sacred Wall

In a levy vote conducted in February 2022, Seattle Public Schools secured $65,500,000 to upgrade Seattle High School Memorial Stadium at Seattle Center. In anticipation of the vote, the City of Seattle (Seattle Center) and Seattle Public Schools signed a letter of intent (LOI) in October 2021, according to which the schools would relinquish control of the parking lot and the stadium while continuing to use the rebuilt stadium for games and graduation ceremonies. According to the LOI, the city would take control of the site, add funds to the levy, and build a new stadium integrated into the Seattle Center landscape. The city also agreed to pay the school district for the revenue lost from the 5th Avenue North parking lot and to give it land for a new high school at the former entrance to the Battery Street tunnel. Now that the levy passed, the city and school district will iron out a final agreement.

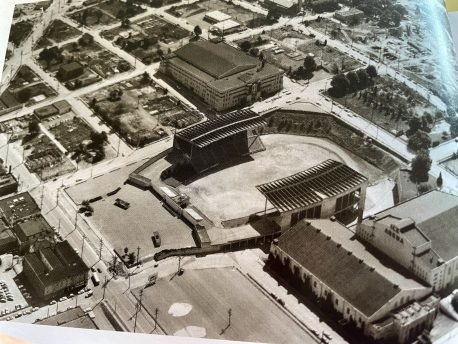

The new stadium will be the third one at this location. The first, Civic Field (aka Civic Stadium), occupied the site from 1928 to 1947, when it was demolished. Civic Field replaced an open pasture located between Republican St. and Harrison St. and 5th Ave. N. and 3rd Ave. N.

Home plate was in the southwestern corner. The field had an extremely hard dirt surface (no grass) and wooden stands on its western and southern sides. Civic Stadium is reputed to have been the most hated place to play baseball in the Pacific Coast League.

The Queen Anne Historical Society recently toured the site in order to take an informed position about whether or not the stadium merits landmark preservation and to assess the potential infringement of a new building on other landmarks at Seattle Center: the Space Needle, the Armory, the Monorail Station, two Monorail cars, and the recently renovated Coliseum (now called Climate Pledge Arena).

Actually, the self-guided tour was limited to the exterior of the huge field and included only one person, me. My stadium experience includes innumerable high school soccer games in the early 1990s during which I was frequently chastised for not attending all of my son’s games. My visits also involved the odd Bumbershoot concert over Labor Day weekends since 1971. Unlike real Queen Anne old-timers, my tour included no memories of the 1962 World’s Fair such as the water-skiing show held four times a day in a special 100,000-gallon tank or the Fair’s opening and closing ceremonies in April and October. I was definitely not one of the 20,000 people who attended Billy Graham’s Revival there on July 8.

Built in 1947 to be the centrally located ‘home field’ for the city’s high school football teams, the site now reads as two primary zones which are in fact separately owned by the school district. The large parking lot on 5th Ave. N. between Harrison and Republican streets is one lot while the stadium with its facing stands and cantilevered roofs and enhanced grassy area on the west end is the other. The stadium is the work of architect George W. Stoddard (1896-1967), a prolific Seattle designer remembered for his 1950 work on the south stands of Husky Stadium. Its dramatic cantilevered roof may have been inspired by the ones at Memorial Stadium. The western segment is enclosed by a wall dating from the Fair and is probably Paul Thiry’s design.

The east, west, and southern sides of the field are significantly lower than most of Seattle Center.

This change in elevation inspired community activists led by David Brewster to suggest a large subterranean garage here. It would have replaced all the public parking structures surrounding Seattle Center and created vast opportunities for new open spaces! I still like this idea and welcome a new stadium as long as it isn’t fenced like the old one is today.

There is little chance Brewster’s fantasy will be realized, but it does suggest that protecting the landmarks surrounding Memorial Stadium will require imagination. Harmonizing with the Gates Foundation buildings and Frank Gehry’s MoPOP (the old EMP) will be a trick, but architects are surely up to that challenge.

The most important design element at the stadium is the memorial wall along the western edge of the parking lot. It lists the names Seattle public school graduates who died in World War II and is the 1949 design of Marianne Hanson (1932-2015), then a student in her senior year at Garfield High School.

The Seattle Daily Times reported on October 7, 1949 that the school board had accepted Hanson’s design. The paper noted that she competed against 59 other entrants and that construction would begin immediately. The newspaper article begins with a call for the 57 names of Broadway High School students or alumni. Their names had apparently been lost when the high school closed and the building served another purpose. In 1949, only the names of the 700 known dead were to be inscribed. The school board planned to pay for the memorial with funds raised at upcoming 1949 Seattle All-State football championship game on Thanksgiving Day and those raised at the game in 1947 and 1948.

The names on the wall include graduates of Ballard (85), Cleveland (28), Franklin (102), Garfield (63), Lincoln (108), Queen Anne (98), Roosevelt (99) and West Seattle (60) high schools. It is unclear if the names of the 57 Broadway High School graduates who died in the war were included on the wall. According to a (renamed) Seattle Times article describing the dedication of the wall by Hanson on May 29, 1951, it was now inscribed with the names of 762 men. Above the list of names, the wall is inscribed with “Youth Hold High Your Torch of Truth and Tolerance Lest their Sacrifice Be Forgotten.”

Standing in the gruesome parking lot as you look west, Hanson’s name appears on the wall's lower right-hand corner. At 17, Hanson understood that a simple design is the best way to honor the men who had died defending our nation. Marianne Hanson later became an important owner of art galleries, first in Seattle, then in San Francisco.

The wall at Memorial Stadium is simply a sacred place. As someone whose father served in WWII and who has close friends whose fathers died in that war, I am adamant that the wall be protected. The new stadium must preserve the wall. A new design would eliminate the rows of automobiles that conceal it, restore the fountains and fluted concave walls that frame them, and eliminate the hedge in front of it that makes in nearly impossible to read all the names.

Designating the wall a city landmark, which happened on October 4, 2023, is the best way to honor the memory of the Seattle high school graduates who sacrificed their lives during WWII and to protect Hanson’s work. It alsocreates a rare opportunity to protect a work that documents the female influence in design which in Hanson’s instance lasted until her death in 2015.